The Squid Fishery and New Zealand Sea Lions

Published: 28 August 2018

What’s causing the decline of sea lions? And what’s the remedy?

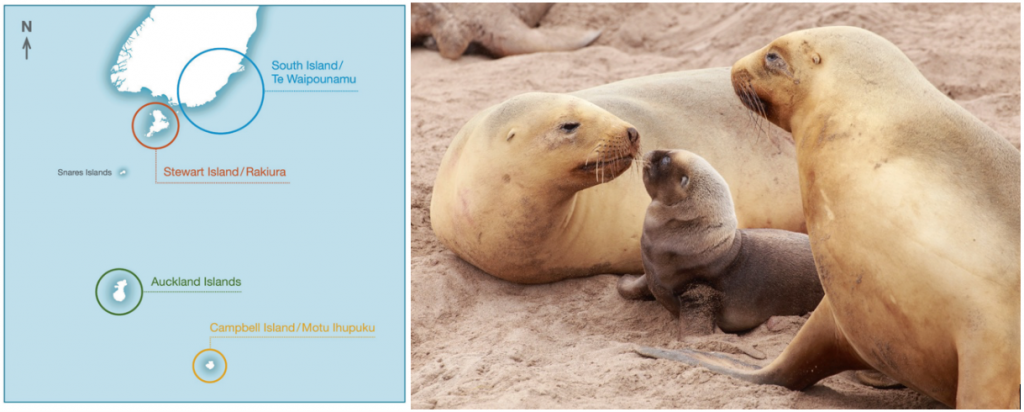

The New Zealand sea lion population at Auckland Islands (Figure 1) is assessed to have declined from around 15,000 animals in 2000 to around 10,000 today – very much a cause for concern. The issue is to determine what the causes of this decline are and to remedy these.

Some commentators have pointed to incidental captures in the squid fishery as the cause. The Auckland Islands’ sea lion population has been well studied over the past two decades, the science undertaken by DOC, MPI and NIWA is comprehensive and robust. The multiple drivers of the decline are now better understood.

Dr Jim Roberts, a scientist specialising in the study of New Zealand sea lions at the NIWA, says: “The most pessimistic view of mortality caused by captures in fishing trawls can only explain a fraction of the decline and it’s clear that something much larger is affecting the sea lions. Low pup survival and the observations of field scientists during the breeding season point to food limitation and bacterial disease as strong candidate causes for the decline.”

Last year, DOC and MPI released their New Zealand Sea Lion Threat Management Plan (TMP), which details a five year plan of targeted research, direct mitigation, and regular monitoring at all known sea lion breeding sites. The scientific assessments that underpin the TMP have assessed the three main drivers of the decline to be:

- A halving of pup survival during the mid-1990s

- A drop in adult survival during the mid-2000s, and

- Low pup production through the mid-2000s.

The observed 40 percent decline in pup production over the decade 1999 to 2009 would require an annual loss of five percent in the number of adult females. Prior to 2006, before SLEDs were introduced, the annual loss of adult females directly due to fishing is estimated to have been around one percent. Since 2006, with the use of SLEDs, annual loss of adult females has declined – it is currently estimated to be 0.17%.

The best scientific estimate of the numbers of sea lions caught in the squid fishery in each of the past 5 years is between one and four adults (based on observed captures, with between 70 percent and 90 percent of tows observed). For management purposes, the numbers of observed captures are scaled up to an estimate of 11 sea lion deaths on average in each of the past five years.

Since the very low numbers of adult sea lions being captured in the squid fishery are not having any material effect on the Auckland Islands population size, clearly we need to look elsewhere for the drivers of the decline.

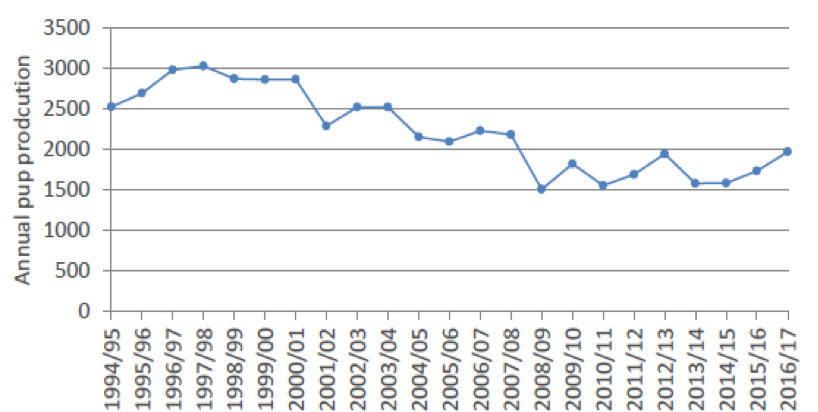

The main concerns are the reduced numbers of pups produced each year and the deaths of hundreds of these pups during their first year. Annual pup production at Auckland Islands declined from a high of 3,000 in 1998 to a low of 1,500 in 2009. It has since stabilized at around 1,500 to 2,000 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sea lion pup production at the Auckland Islands 1994-95 to 2016-17. From Roberts & Doonan (2016) Quantitative Risk Assessment of Threats to New Zealand Sea Lions. MPI AEBR 166

The effects of the loss of so many pups over recent years will take time to work through to the breeding population. Sea lions start breeding when around five to six years of age and may breed for up to 15 years. Even when pup survival returns to ‘optimal’ levels, there will inevitably be a time lag before this translates into increased numbers of breeding females and increased pup production, because of the time taken to reach breeding age.

If we wish to assist this sea lion population to thrive, the questions that remain are:

- What caused the drop in pup production and survival over the past 20 years?

- What options do we have to intervene or to reduce these causes from impacting further on this population?

The most obvious causes of decline in this population are disease (Klebsiella Pneumoniae in particular); pups getting stuck in mud holes and drowning or starving; adverse environmental changes; food availability; increased predation (particularly by sharks feeding on juvenile sea lions); and direct mortalities of adult females by fishing.

Although fishing is not the biggest threat to the sea lion population, the industry is still doing all that we can to avoid interactions with sea lions and we are committed to ensure sea lion populations thrive. We are active in their conservation and in reducing the numbers being caught in our nets.

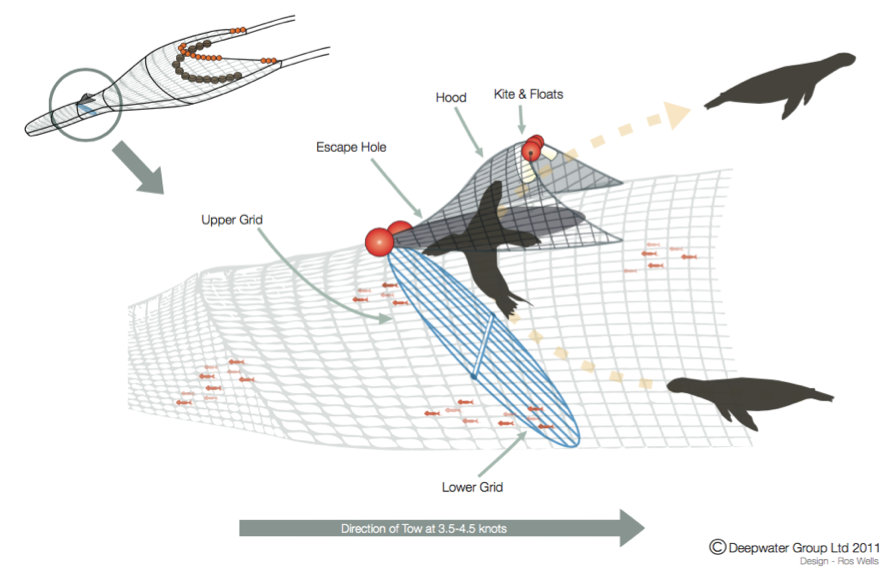

The fishing industry developed and deployed Sea Lion Exclusion Devices (SLEDs) in trawl nets and these have been proven to be effective. In addition, industry both funds and actively supports scientific studies, pup counts, disease research and measures to reduce pup deaths in their colonies.

All vessels in the squid fishery are now equipped with SLEDs, which allow sea lions to easily escape from the net (see Figure 3 and this animation explaining how a SLED works). All SLEDs are audited to ensure they meet agreed specifications and their use is monitored at sea by MPI and DOC.

We’re often asked why the fishing industry doesn’t jig for squid, instead of trawling. The simple answer is that jigging has been trialled here and is not economic in the extreme open oceanic waters and sub-Antarctic weather. In the past, squid jigging has been successful elsewhere in New Zealand waters, but the charter of foreign-owned fishing vessels is no longer permitted by Government.

What clouds the arguments about sea lions are claims by parties, mostly outside of this process, who allege that fishing mortalities are the significant cause of the decline of this population size. These allegations are not supported by the best available science. Scientist say that those squarely pointing the finger of blame at the fishing industry for the decline in the Auckland Island sea lion population are operating under a number of myths.

Myth No. 1: Sea lions eat mainly squid so they are competing for food with the commercial fishing vessels. Not true - squid make less than one fifth of sea lions’ diets.

Myth No. 2: SLEDs are contributing to sea lion deaths as animals drown or die from injuries after interacting with SLEDs. Not true – a risk assessment of SLEDs carried out for the TMP looked at the effects of commercial trawl mortality, including the most extreme scenario: if 100 percent of adult sea lions interacting with trawl gear died, all of their pups ashore died, and all future pups were lost. Even this worst case scenario does not explain the population decline.

Myth No. 3: Bacterial disease has not killed many pups since the acute epidemics in 2002 and 2003. Not true – Klebsiella Pneumoniae is now endemic (a constant presence) in the population and is the biggest killer of pups. Hundreds die each year.

Figure 3: Sea Lion Exclusion Device. Source: Deepwater Group.

No conservation matter – nor threatened species – is best served by untruthful agendas. Good science must always be at the heart of all that we do. Dr Jim Roberts has said: “Misinformation is a genuine threat to the conservation of New Zealand sea lions. Thankfully, we have a wealth of information and we need to make best use of it."

What can be done about two of the major factors identified in the TMP – the large numbers of pup deaths due to disease and due to starvation or drowning?

Scientists have advised it might be possible to develop a vaccine for Klebsiella Pneumoniae but that it would be both expensive and challenging to inoculate a wild population.

Starvation or drowning all too often results from sea lion pups falling into deep or steep-sided holes and wallows from which they are unable to climb out. The TMP will expand the ‘Planks for Pups’ programme, a simple but effective measure that places ‘planks’ on the side of these holes to enable pups to escape.

The TMP also directs resources into research on disease in the population, into nutritional stress, and into the diet of adult females.

As Dr Jim Roberts has said: “The Auckland Islands population has been dealing with something much bigger than trawl mortality and we urgently need to know what this is.” And, "Real progress been made to understand the decline at the Auckland Islands in recent years, including the twin roles of bacterial disease and food availability, in addition to better understanding the effect of captures in commercial trawls.”

The Auckland Islands sea lion population decline is concerning – but there are positive signs that conservation efforts are working. In the 2018 season, pup production was 2,000 – up from the lowest count of 1,500 in 2009.

Also encouraging are the recolonisation of sea lions on Stewart Island and on the New Zealand mainland over the past 20 years. The Campbell Island population size (where a third of all pups are now born) is increasing. Multiple breeding sites helps protect a species against catastrophic events.

But half of the pups born at Campbell Island have been dying in the first few weeks – likely due to starvation and drowning. This clearly deserves remedial attention. Because of their close proximity to humans, the Stewart Island and mainland populations face a very different set of threats.

The New Zealand seafood industry remains committed to not only reducing its own risks of harm, but also to assist in real world efforts to find and address the causes of sea lion population declines…and to restore New Zealand sea lion populations to safe levels. This goal is achievable, given concerted efforts by all, and is supported by signs of positive progress over recent years.

George Clement, Chief Executive, Deepwater Group.

As originally published in Professional Skipper Sept/Oct 2018 issue.